“Walls Get in the Way of Collaboration and Creativity”

Dartmouth's reimagined West End is flourishing as an inclusive crossroads of teaching and research with impact.

Aug 27, 2024

7 minute read

James Bressor

7 minute read

“Proximity matters,” says Thayer School of Engineering Dean Alexis Abramson.

That’s a neat, two-word summary of the promise Dartmouth made during The Call to Lead campaign as the university introduced the idea of a technology-focused district on campus.

By locating engineering, computer science, energy, and business next to one another, Dartmouth pledged that this new district would be a place of serendipitous collisions, with faculty from across disciplines discussing novel ways to collaborate on research with global impact, and it would be the epicenter for expanding the tech literacy of all Dartmouth undergraduates—essentially redefining what a liberal arts education means today.

The concept of what would become known simply as the West End grew out of multiple campus facility needs. Coming into the 2015–16 academic year, the number of engineering majors had doubled since 2005; enrollment in computer science courses had doubled during the previous five years; and the Dartmouth Entrepreneurial Network (DEN), a four-year pilot program, was expanding quickly and attracting many students and faculty, outgrowing its location south of Lebanon Street.

Constructing individual new digs for each of these programs might have been the obvious solution. Instead, given the disappearing distinction between the computational and physical elements of devices and the possibility of establishing a new kind of energy institute thanks to a generous donor, Dartmouth took a different tack. The decision was made to develop a technology-focused hub for innovation at the west end of Tuck Mall. This newly designated area would colocate computer science, a large portion of Thayer, and the DEN—which would become the Magnuson Center for Entrepreneurship—in a single building and place the energy institute next door.

Within six years and with a philanthropic investment of more than $360 million, Dartmouth constructed and dedicated two spectacular West End buildings: the Class of 1982 Engineering and Computer Science Center and the Arthur L. Irving Institute for Energy and Society. While they are dramatic physical additions to campus, their real impact is seen in the interdisciplinary teaching and research, involving students and faculty from nearly all majors, made possible by colocation.

The Arthur L. Irving Institute for Energy and Society, lower right, and the Class of 1982 Engineering and Computer Science Center, upper left, anchor the reimagined West End.

Early days, clear trend

In the life of a university founded more than 250 years ago, these buildings are still youngsters—both opened within the past three years—so it’s too early to gauge their full impact. However, the trend is clear.

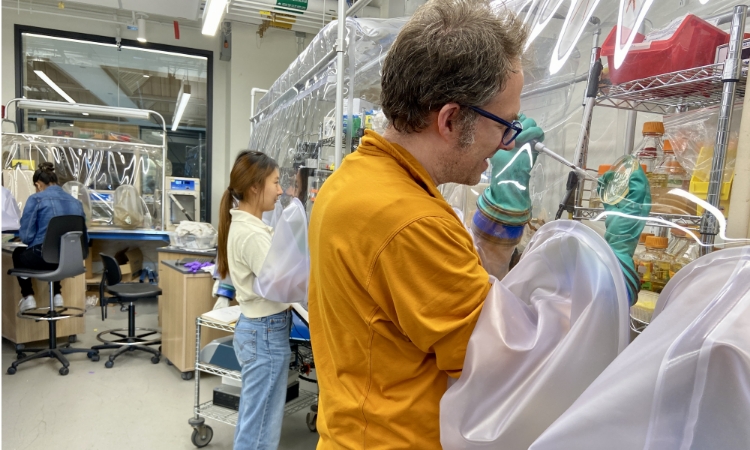

Abramson says she is seeing more interdisciplinary grant submissions, and the open-design labs, shared by multiple faculty members, are fueling collaborative work into areas such as protein engineering, vaccine development, and artificial intelligence. As an added bonus, and as predicted, the West End is attracting a wider range of undergraduates.

“Previously, we didn’t have a home for the Design Initiative at Dartmouth, which is a cross-campus initiative engaging faculty, students, and staff from all over campus. Human-centered design is now the number one minor on campus, and students from more than 20 different majors are minoring in HCD,” says Abramson. “They’re all coming to the Engineering and Computer Science Center, and they’re all bringing their friends.”

With more students coming to the West End, there are more would-be entrepreneurs curious about the possibility of turning a concept into a venture.

“Students often come to me saying they have an idea and asking, ‘What should I do?’ Now, I can answer, ‘Well, walk down this hallway and through that door.’ And then they sign up for a workshop at the Magnuson Center,” says Abramson. “We’re able to bring entrepreneurship much more easily into our conversations because the resources are right here.”

Jamie Coughlin, founding executive director of the Magnuson Center, was certain moving to the West End would accelerate the center’s growth. It has surpassed expectations.

“Our collective efforts to grow entrepreneurial thinking throughout the Dartmouth community have exceeded our original vision. In fact, we have already outgrown our space in the ECSC, and now are retrofitting and opening a space in Murdough Hall, which is attached to the energy institute,” he says. “The advantage of being in the West End is twofold. First, we’re now more integrated into the campus generally, and second, we’re more closely connected with and invested in the builder community, specifically engineering and computer science.

We serve all students, faculty, staff, and alumni, but it is the builder community that is such a critical ingredient for the work of entrepreneurship because you need people who can realize ideas and build the actual product.”

Coughlin emphasizes how Magnuson weaves the work of multiple disciplines, connecting people and programs across interest areas.

“An element of our ability to activate entrepreneurship across Dartmouth is the fact that we work horizontally across the institution. We are open and accessible to all and work hard to find non-obvious points of intersection,” he says. “That’s where the magic happens.”

Startup accelerators—with Magnuson providing researchers with the support, entrepreneurial guidance, and infrastructure needed to bring ideas to the marketplace—have proven to be particularly effective. Under the Magnuson Center’s guidance, Dartmouth has launched accelerators focused on cancer, digital health, and climate change.

The Arthur L. Irving Institute sits between Thayer and the Tuck School of Business, and, in many ways, it is the West End’s interdisciplinary lodestone. The institute isn’t affiliated with a single academic discipline, so nobody feels like an interloper; energy issues appeal to a broad mix of students and faculty; and having an attractive café with a stunning view of Baker Library brings more people through the building’s front door. The institute leverages its central location to foster partnerships across schools and departments, supporting education and research aimed at decarbonizing the global economy.

Geoffrey Parker, interim faculty director at the Arthur L. Irving Institute, says a working group that included Abramson, Paul Danos Dean of the Tuck School of Business Matt Slaughter, and several faculty members has just completed a strategic plan that will guide the institute’s growth through 2030.

“The research side is starting to pick up steam, but I’d say it’s probably the area that needs to be most developed. As part of the strategic plan, we’ve identified focal areas where we have strength and we can be nationally and internationally visible and impactful,” he says. Two of these interdisciplinary research topics are developing technologies to reduce or capture carbon and harnessing artificial intelligence to advance the energy transition, such as better management of the North American power transmission grid. Another emerging subject where Dartmouth possesses expertise is health and equity in the energy transition; Parker says about three dozen faculty across schools and departments are in conversation about this broad concern.

Angie Hofmann, director of research programs at the Arthur L. Irving Institute, says she and her colleagues have identified more than 200 Dartmouth faculty whose research touches energy, climate, and sustainability topics, and they represent nearly all disciplines, including the humanities, arts, social sciences, sciences, engineering, and medicine. With this depth and breadth of expertise, faculty are exploring myriad issues intertwined with the clean energy transition. For example, there are many unknowns at the intersection of energy and health that can be mitigated with data-based research. They include access to heating and cooling solutions and illnesses that may arise from exposure to energy-intensive activities such as transportation and power production.

“Many pulmonary problems and certain cancers have been associated with emissions from fossil fuels, which drive climate change. In addition, heat exhaustion and heat stroke are among the most visible health impacts of climate change. Heat also affects our cardiovascular system,” she says. “At the same time, we need to be aware of materials that are being used for new energy sources. We want to identify and use benign substances when developing new technologies so that the energy transition results in net benefits for human and environmental health.”

While some research activities are still in their nascent stage, the Arthur L. Irving Institute is benefiting students in multiple ways, including new courses and experiential learning opportunities. Parker notes that the institute annually grants about $130,000 to 40 to 50 students for various activities, including attending conferences and pursuing academic research. Additionally, the institute provides approximately $500,000 in competitive faculty seed grants to encourage collaborations across schools and departments, focusing on developing solutions to challenges at the nexus of energy and society.

The atrium in the Arthur L. Irving Institute for Energy and Society offers a popular place for students, faculty, and staff to meet.

A sampling of initiatives

West End partners have launched—or at least have begun developing—multiple new interdisciplinary programs, courses, and degrees in the past two years. Here is a sampling:

Design Ethics, developed by the Design Initiative at Dartmouth, is a new engineering course exploring the moral, social, and environmental responsibilities of designers and helping future designers avoid unintended consequences that come from invention.

Arthur L. Irving Institute staff are planning a Master of Energy Transition degree that will draw on faculty from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Thayer, and Tuck. Parker says a small number of universities offer similar degrees, but they tend to be housed strictly within a business or engineering school.

The Magnuson Center led the creation of Dartmouth’s new Social Entrepreneurship course, which brought together the Rockefeller Center, Tuck, and the Department of Economics. “We built the roster, we helped with the syllabus design, and we paid for the course,” says Coughlin.

TuckLAB: Energy and TuckLAB: Entrepreneurship are co-curricular programs that help prepare students for energy-related careers or entrepreneurial endeavors by leveraging Dartmouth’s liberal arts and business strengths. Through a team-project approach, students explore issues such as policy, finance, venture creation and funding, organizational change, equity, and justice as they investigate complex challenges and opportunities. The programs are supported by multiple partners, including the Magnuson Center, Arthur L. Irving Institute, and Tuck’s Undergraduate Programs Office and Revers Center for Energy, Sustainability, and Innovation.

Dartmouth’s Energy Justice Clinic pairs students with community partners to explore ways to make energy systems more inclusive, equitable, and just. The clinic has connected students with communities in the Upper Valley and in South America.

Greenshot, Dartmouth’s accelerator dedicated to climate change solutions, culminated its past year’s pitch competition for aspiring entrepreneurs in New York at the spring Dartmouth Entrepreneurs Forum. Created and led by the Magnuson Center and the Arthur L. Irving Institute, and in partnership with Thayer and Tuck, the competition awarded $75,000 to Mach Electric, a startup developing technology to produce carbon fibers from industrial waste.

Each of these activities represents what the West End was intended to be: a silo-free, forward-looking, inclusive crossroads of teaching and research, driving positive change with broad impact.

“We designed these buildings with as much shared space as we could, even in the laboratories. An example is our biological and chemical engineering faculty sharing a big open space, which is highly unusual—you wouldn’t see that at most schools of engineering. But walls get in the way of collaboration and creativity,” says Abramson. “These buildings give faculty, students, and staff more opportunities to connect with one another. If you walk into either new building, you just feel very inspired.”